A new day is here!

The most beautiful cry.

SUNNY MORNINGS are a fiery sword, a single blow brings you to paradise! There should be a thousand words to describe such beauty. The sun rises above the mountain plains, a morning firebird. It soars, silent and dazzling. You have just awakened, born anew. A new day has begun; a new day in which anything can happen.

Sleep under an open sky when nights are clear. Only then will you wake before the sun has risen. You open your eyes to a pale dawn. Your sleeping bag is heavy with moisture, but you lie within, cloaked in your own warmth. The night’s chill still lies in the grass, and dew falls from the heavens. With each movement, a cold shiver runs through your body – better to rest still and quiet. Only your eyes gaze up at the pale, tranquil sky. Suddenly you experience the same second of joy as the Eskimos when, high up in the black sky at the end of the polar night, they spot a gleaming white bird. The first solitary bird returning north after winter! In the land of the Eskimos, it remains dark and cold and the sun still stays below the horizon. But from below, it sends forth the first ray, months unseen, weeks awaited, illuminating the breast of the flying bird. The first ray in the darkness! The white arctic bird wings silently through the air, oblivious to its dazzling prophecy, but down below, the people cheer, cry, jump and shout: the sun, warmth of life, is returning.

You, too, little brother, can see a little greenish cloud appear on the pale sky just above the northeastern horizon. It scuds alone across the sky, far and wide the only cloud. As of yet, no sight of the sun. But lo, while the back of the morning cloud remains in darkness, its belly has already begun to gleam. For he who shows and aligns its heavenly track has now begun to illuminate it with his glow. A new day is dawning in which anything can happen. Even death may come as you wait for night. Sleep, too, is a short death. But now a new day has come!

The cloud dissolves in the radiance of the rising sun. You lay wrapped in your sleeping bag, nostrils taking in the ever more fragrant air, eyes gazing into the brilliance which is still bearable. You smile your happiness – you have awoken to a sentence from the Hindu Upanishads which says that he who dwells within the sun dwells also within man. They are one. At these moments it is best to sing a morning song of celebration and thanksgiving if you know one. And if you do not, my impious little brother, make one up for it is sure to come useful. Steam is now rising from your sleeping bag as the fiery bird flaps ever more ardently, drawing from you the dewy damp of the night. Now you can finally move in your sleeping bag. Spread out lazily inside it. The cold shiver no longer runs through you, and the heavens rain down ever growing heat. Soon you will once more be unable to move – not for cold, but for warmth – for you will be doused in a sweltering humid cloud. As the sun rises, so does the temperature. Suddenly, the moment arrives when you can no longer bear another second in your sleeping bag. You tear it off, but you are still too hot. Unable to stand the heat, you strip off your clothes.

How wonderful to be on the plains alone. You can lay naked upon your sleeping bag, immeasurably relieved. The sun sings to you, the silky air gently fans you, and flies, first of friends, settle upon you. Do not chase them away, for they sing to you and lap you with their tongues. It delights them. Be grateful when you can delight someone, little brother, there may come a day when you would give your eyeteeth for that! The wind rises. Brother wind. Balmy, but the flies take to the air. How wonderfully un-European to lay naked in wild pastures. Laid bare to the sky. There is so much our ragged garments withhold from us!

And if, with the morning sun’s return, you are not alone? All the better, especially if you wake beside a shiny-eyed girl with a nose as gentle as a foal’s. Perhaps it is she will enkindle the lamp of love, that rosy glow that gleams so rarely in life, sometimes only for a second, sometimes only once, sometimes never, but which is always worth trudging the world for. You will never forget it. The universe hauls up its anchor for a voyage that is eternity in a single second. Shivers up and down your spine, tears of joy. A quiet ringing in your head, a murmuring and chiming, rosy light as you gaze upward through shut eyelids. The fullness of everything. You touch her gently, and the moment comes. The world is bathed in apple-blossom light. The ark of bliss rocks upon sunlit waters. This light, which comes always unexpected and unsummoned, shines elsewhere, too – in the deepest of monastic solitudes, on the peaks of great mountains, on Olympic pedestals before crowds of thousands, above a completed masterpiece, in a shepherd’s song, at a ship’s sailing. But most often, it is borne by girls, fragrant, light-legged light-bearers; fragrant, light legs play their oldest and most beautiful game.

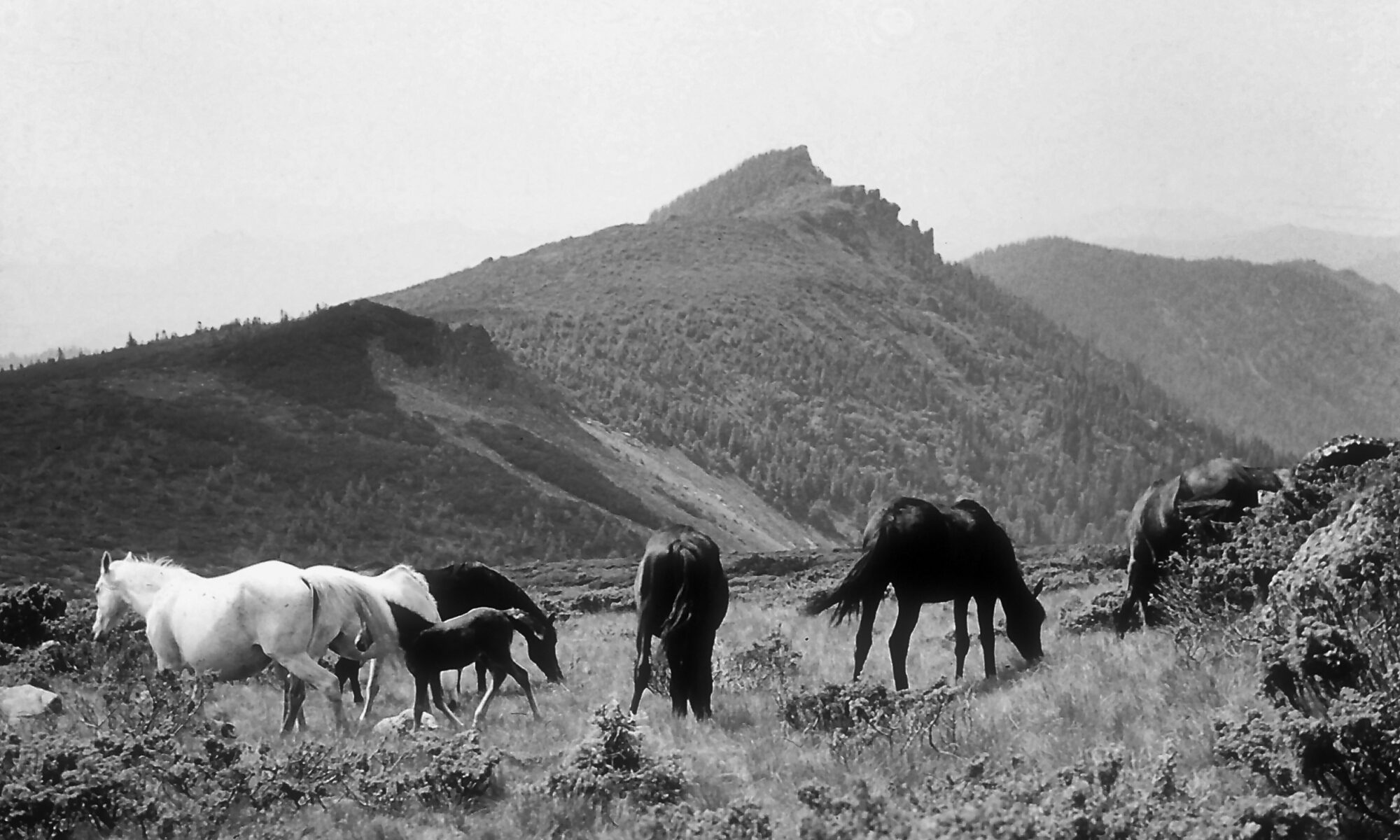

Making love in the morning is the most beautiful thing of all. So pure. With a girl whose eyes are like the sea. On the open plains in the embrace of the eager sun. Like wild horses, whinnying, manes flying. There, all cries dissipate. I hope it is no sin. It was not I who breathed into girls their wild fragrance or gave them such sultry skin. He who dwells within the sun dwells also within girls. On such amorous mornings when the sun hangs in the blue like a flaming tine, I think it better to make love just once in with a wild southern princess and die as punishment than a thousand times embrace a lethargic lemur. That a single scintillating year is better than fifty dull ones, and one day of fire is worth ten thousand days of darkness. Worry about today, little brother, tomorrow will take care of itself! But I don’t think that always, for the hot sun does not always blaze above open plains.

But beautiful mornings need not be lived only under the open skies of distant journeys, my life-weary little bother! A new day rises even amidst November’s gloom and chilly winds. Astonishingly, most people hate mornings, they hate waking and rebirth. They do not prattle on gleefully, but shuffle gloomily around the house in fear of the new day – old men and women lost to hope. They know too well how the day will end. Yet turning mornings gold and days to silver is such a simple task. It requires but three things: a song of thanks, a cold bath and exercise or a wild dance. Three offensively simple things can change the world! Dismal thoughts and dreariness vanish, and strength and happiness swiftly take their place. Just three things – a song, a little water and a bit of movement – and mornings are transformed. Yet I know I write these words in vain, my life-weary brother, for you will not change – you will not even try it!

I walk along a morning street. Looking round, I see it is empty. So I dance my morning dance. I whirl around gleefully, stamping my feet because that is the only dance I know. It is a new day. The street is still empty. So I bleat loudly. Like a goat. Meehhh! A prostatic Prague Ratter urinates at length beneath an ash tree, I greet him in my best Frrrench: “Bon jour, mon ami, ça va?” And the street is still perfectly empty.

A morning song, a cold bath and a bit of exercise make you feel strong and healthy. Indomitable of body, insurmountable of soul. You can sit motionless, hands on the table, and yet feel as strong as a snow leopard, the most beautiful of animals. Of their own accord, the muscles in your back begin to coil. If you make a fist, no earthly power can unmake it against your will. You sit motionless like a leopard in wait of a mountain sheep, prepared to leap, full of explosive energy, yet seemingly inert. Resting on the snow, it looks like a boulder. You, too, sit quietly, but warmth and power emanate from within you, it is a wonderful feeling. At that morning hour, the entire world is yours. You sit alone, insignificant and unimportant, no one knows you exist. And yet on such mornings, the whole planet belongs to you.